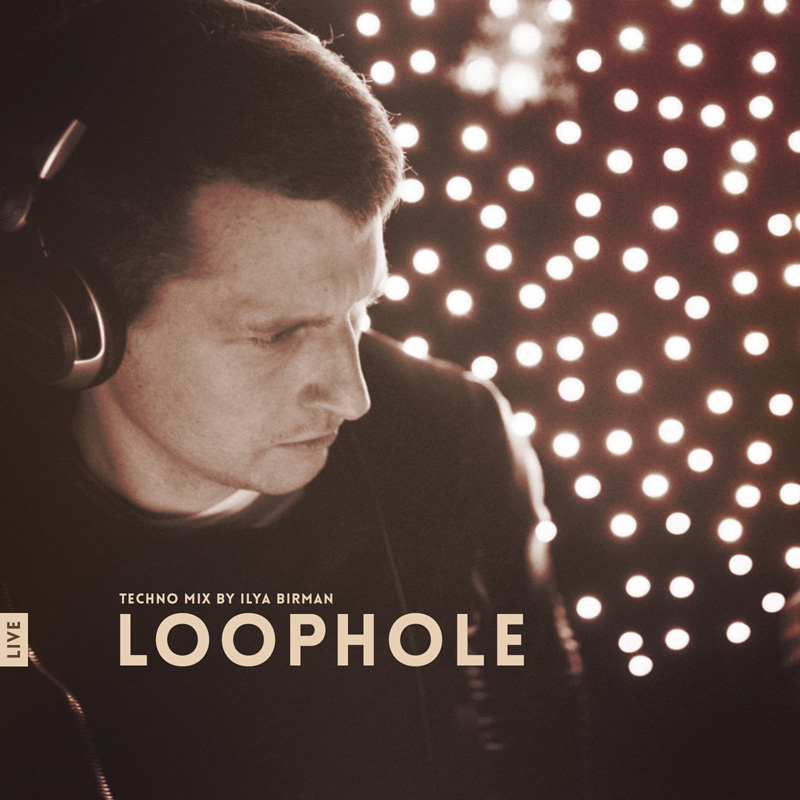

Live mix: Loophole

This saturday I played techno in Bukowski Bar:

The playlist:

| 0:00:00 | Rekord 61 | Sverh (Radio Slave FYM Remix 2) |

| 0:01:52 | Pig & Dan & Alberto Ruiz | Truenos (Original Mix) |

| 0:06:05 | Fixon | The Pain Is Gone (Audio Injection Remix) |

| 0:07:43 | Israel Toledo | Standing |

| 0:11:22 | Martin Eyerer & Florian Meindl | The Rush (Original Mix) |

| 0:15:31 | Filterheadz | Music Saved My Life (Original Mix) |

| 0:18:55 | Nastia Reigel | Figures in Brine (Truncate Repaint) |

| 0:22:50 | Cirez D | On Off (Original Mix) |

| 0:27:44 | Reinier Zonneveld & Axan | Loophole (Original Mix) |

| 0:31:32 | Phunk Investigation | Noizer (Original Mix) |

| 0:35:24 | Sam Paganini | Dusty |

| 0:39:03 | Petter B | Voltage Controlled Time (Original Mix) |

| 0:43:43 | NoizyKnobs | Really Deep |

| 0:46:29 | Orion | Forerunner (Jerome Sydenham & Janne Tavi Remix) |

| 0:50:54 | Woo York | Siberian Night |

| 0:54:35 | Developer | Catch My Flow |

| 0:58:21 | Cirez D | Glow (Original Mix) |

| 1:03:09 | Tensal | Achievement 3 |

| 1:05:37 | Stanny Franssen | Bionical Clones |

| 1:08:09 | Norbert Davenport & Robin Hirte | Tijuana Mode |

| 1:12:04 | Spark Taberner | Meteors |

| 1:17:06 | Robert Hood | Power To Prophet |

| 1:21:37 | Marco Bailey | Night Attack (Sian S Calpol Mix) |

| 1:24:24 | Adoo | Drumigos (Original Mix) |

| 1:28:18 | Marcel Dettmann | Linux |

| 1:31:14 | Fixon | Detachment |

| 1:34:37 | David Moleon | Pasive (DJ Lukas Remix) |

| 1:36:45 | Dustin Zahn | Sunday Night Fever (Original Mix) |

| 1:39:39 | Vegim | Thorazine (Original mix) |

| 1:43:14 | Unam Zetineb | Transmissions |

| 1:46:57 | Alan Fitzpatrick | Turn Down The Lights (Original Mix) |

| 1:50:14 | Birth Of Frequency | In Their Steps |

| 1:55:12 | P.E.A.R.L. | Desolation (Reeko Deep Version) |

See also a Mixcloud page.