Most web pages don’t load pleasantly. Loading takes time, images and other elements appear in a random order. Content jumps when new elements load above it. Some things are unreadable before a font or a background is loaded. We are used to this.

Desktop apps are different: an app’s user interface would appear only after it’s loaded. The apps that are slow to load show splash screens.

The desktop approach looks more polished. But on the web, we can start reading and even using a page before it’s fully loaded.

How can we take the best of the two worlds? We can gradually show a page, but make sure it looks fine at every step of this progressive loading. And we’ll try to minimise the jumping. I call this “coordinated loading”.

Emerge is a JavaScript library that I’ve created to help add coordinated loading to your website. Normally you would need to manually write a lot of code to do this. But with Emerge, you just specify the desired behaviour with HTML attributes. Let’s see how you can use it on your website.

Prepare: provide boxes for images and other external objects

Before we even start using Emerge, let’s fix one thing. Consider this code:

<img src="some.jpg" />

<p>Text</p>

Before the browser has loaded the image, it has no idea how much space to provide for it. So it first just shows the text as if there was no image. When it starts loading the image and figures out its size, the layout changes for the image to fit. So the text jumps down.

To avoid the jumping, specify all images sizes:

<img src="image.png" width="200" height="300" />

<p>Text</p>

Here’s how you can do this with PHP (5.4 or later):

<img src="image.png" <?= getimagesize ('image.png')['attribute'] ?> />

<p>Text</p>

But what if you want an image to be flexible, i.e. occupy 100% of the container width?

<img src="photo.jpg" width="100%" />

In this case, to avoid the jumping, you’ll need a container with fixed proportions. Let’s say you have a 3:2 photo. Here’s a way to do it:

<div style="position: relative; padding-bottom: 66.67%">

<img style="position: absolute" src="photo.jpg" width="100%" />

</div>

Paddings’ percentages are always percentages of width, even for vertical padding. So the div will have 3:2 proportions even before the photo is loaded. PHP code:

<?php $size = getimagesize ('photo.jpg'); ?>

<div style="position: relative; padding-bottom:

<?=round (100*$size['height']/$size['width'], 2) ?>%">

<img style="position: absolute" src="photo.jpg" width="100%" />

</div>

The same can be done with videos.

Figure out which elements of the page make no sense unless they are fully loaded

OK, appearing images will no longer cause jumping. That’s a win already.

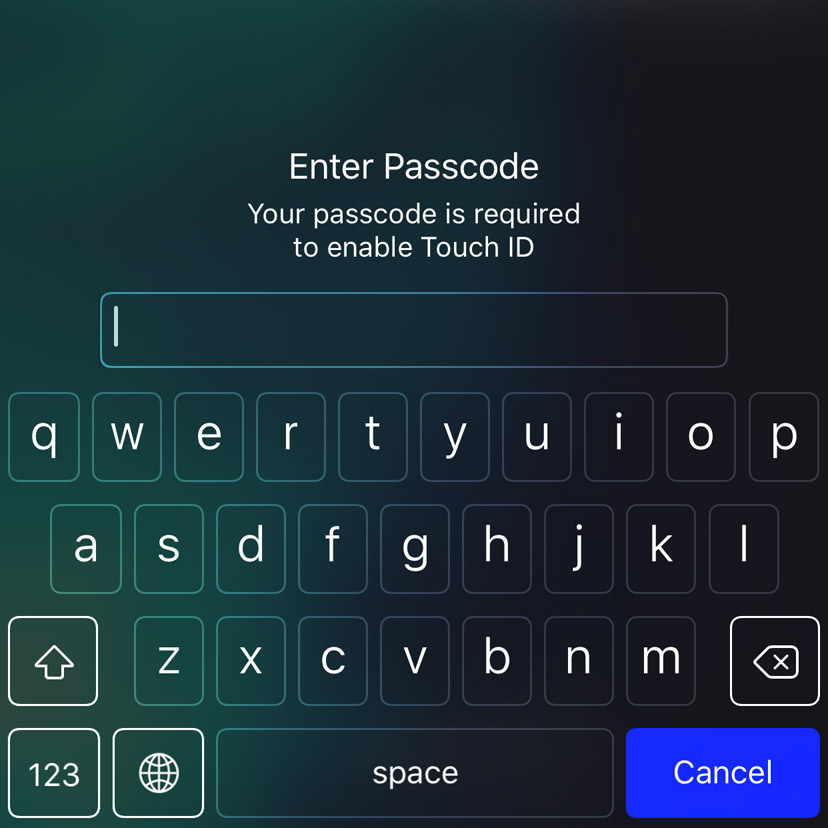

But with the Emerge script added to your page, you can do more. Use class “emerge” in an image to make it fade in (“emerge”) when loaded:

<img … class="emerge" />

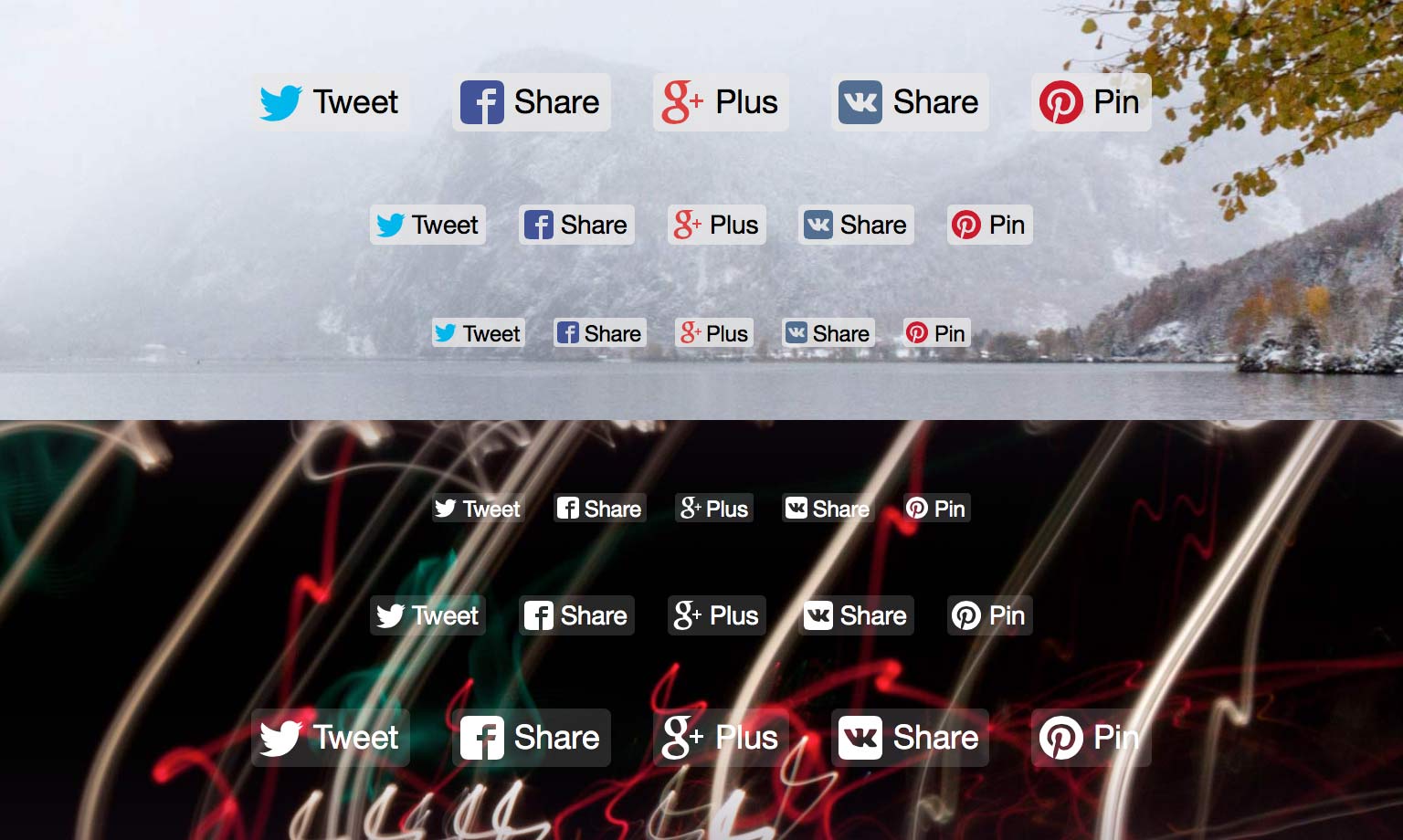

What if your image has a caption which makes no sense unless the image is loaded? Actually, you can wrap elements in divs with class “emerge”:

<div class="emerge">

<!-- Text, images and what not -->

</div>

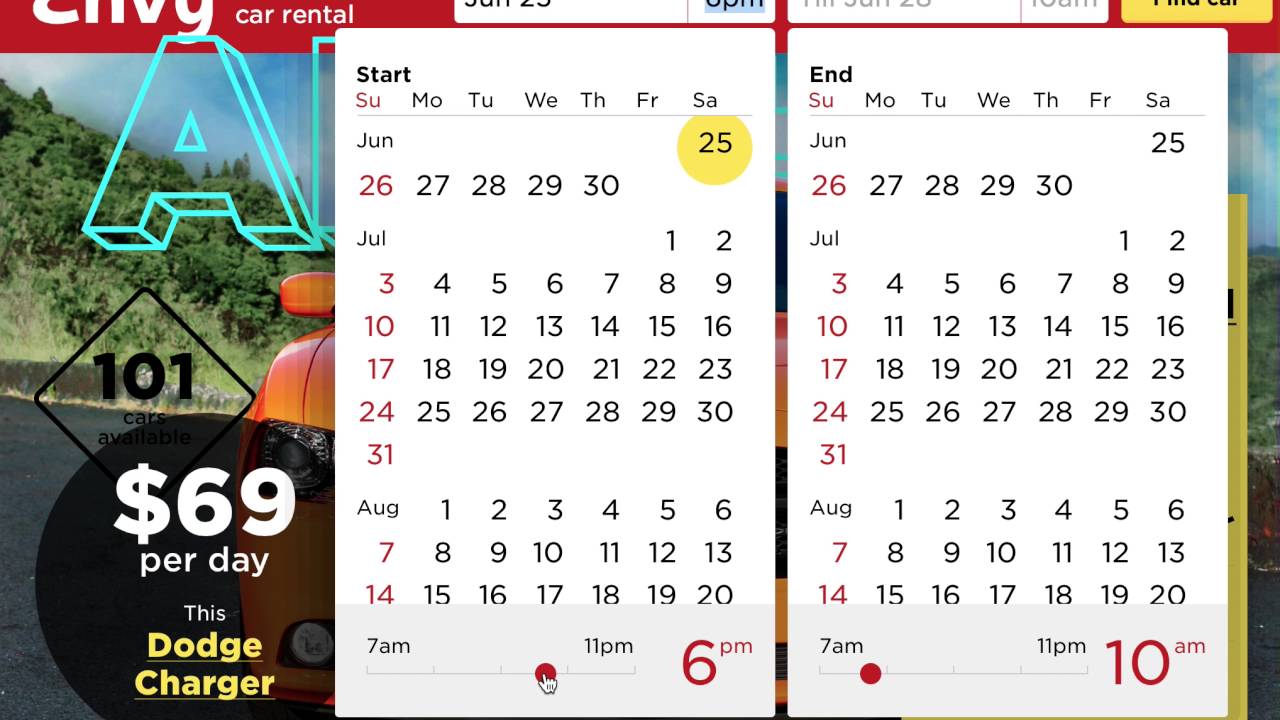

You can put multiple images and videos into such div. The div will emerge only after all images and videos inside it are loaded.

Add a loading spinner for large elements

Some of your emerge elements may be quite large and take considerable time to load. The user may be confused by a large empty space on a page. So you can ask Emerge to display a loading indicator while such elements load:

<div class="emerge" data-spin="true">

<!-- Show spinner while this is loading -->

</div>

Emerge has a built-in spinner with variable size, color and spin direction. If you want a custom spinner, Emerge supports them too. The documentation explains spinners in detail.

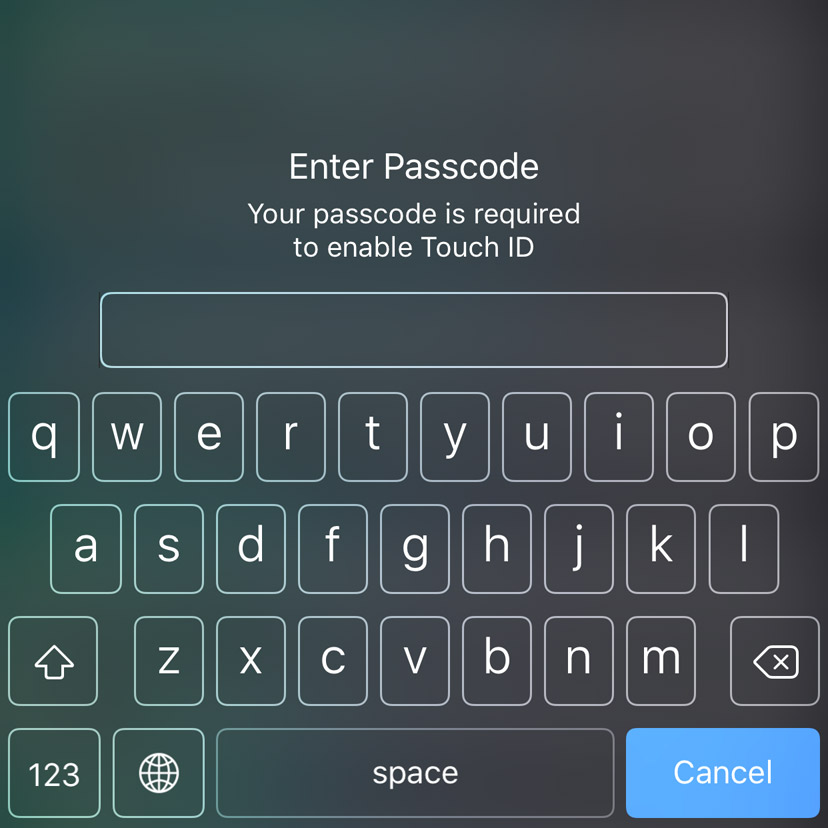

Make sure things appear in order

It may happen that an element which is lower on a page loads and emerges before the one which is above it. This may look strange and you may want to make sure the element load in a particular order.

Here is the easiest way to make an emerge element wait for the previous one to load:

<div class="emerge">

<!-- Some content -->

</div>

<div class="emerge" data-continue="true">

<!-- This will wait for the previous element to emerge first -->

</div>

The attribute data-continue means that even when this element’s images and videos are ready, it would emerge only after the previous one. You can chain many elements this way. If document order is not what you want, there is also a way to make one element wait for a particular other element by its id.

Select effect that make your site look best

By default, elements emerge by just fading in. But this is also adjustable.

Here are some examples of what you can do. You can make an element slide horizontally or vertically while it emerges:

<div class="emerge" data-effect="slide" data-up="20px">

<!-- Stuff that will slide up 20px while emerging -->

</div>

Use data-down, data-left or data-right to change this. You can combine a horisontal and vertical parameters for diagonal motion.

Or you can make an element zoom-in:

<div class="emerge" data-effect="zoom">

<!-- This will zoom in while emerging -->

</div>

Tune the original size with data-scale=“0.8” (or another value).

You can control an animation duration with data-duration (in ms).

There are other effects, which you can read about in the documentation. You can also provide an exact CSS for initial and final animation states.

Experiment and have fun

Since Emerge does not require you to write JavaScript, it’s very easy to experiment with. Find the way for your website to load in the best possible way.

But make sure you use the effects to improve the way your site loads, not make it too flashy and distracting. Don’t wrap the whole page into an emerging div: the user won’t see anything before everything is loaded, and your website will feel very slow.

The idea is to find elements that make sense only as a group, and make such groups appear in a single fade-in animation when ready. And then coordinate the order and motion for these groups.